Perceptions of Men’s Mental Health in the Workplace: A Case Study of Construction Workers in North-West England

Perceptions of Men’s Mental Health in the Workplace: A Case Study of Construction Workers in North-West England

Faye Boswell and Dr Victoria Jackson,

Liverpool Business School, Liverpool John Moores University

Background Context and Rationale

Poor mental health and wellbeing amongst employees causes wide-reaching negative impacts within the workplace, by affecting an individual’s propensity to work effectively and productively (Sharac, Mccrone, Clement & Thornicroft, 2010). The construction sector is an industry that demands high levels of productivity and efficiency yet suffers from some of the highest numbers of mental health issues coupled with negative perceptions of help-seeking behaviours (Kotera, Green & Sheffield, 2019). It is estimated that 97% of construction workers suffer from high levels of stress and feel pressure within their role, resulting in construction workers being three times more likely to take their own lives compared to other industries (Rees-Evans, 2020). As such, there is a clear urgency to gain a better understanding of men’s mental health within the construction industry (Seaton et al., 2017).

Prior to 2020, there had been relatively few studies which explored mental health within male-dominated sectors (Burki, 2018; Seaton et al., 2019). From January 2020 however, several publications started to emerge with a specific focus on mental health in the construction industry. Firstly, a global perspective of mental health in construction was offered by Chan, Nwaogu & Naslund (2020), who set the scene by providing an appraisal of the risk factors for poor mental health in the construction industry internationally. Secondly, a Chartered Institute of Building (CIOB) report focusing upon the UK, stressed that “mental ill-health is a silent crisis within the construction industry….workers often suffer in silence, and the ‘macho’ culture of simply dealing with it and not seeking help only makes the issues worse� (Rees-Evans, 2020). Thirdly, Campbell and Gunning (2020) concluded that for the UK “a focused and industry-wide effort to change the mindset of workers through effective strategies, policies and management practices will improve the health and well-being of the industry as a whole�. This sudden increase of research into this field, demonstrates the urgent need to address mental ill health in construction, which has consequences ranging from individual sufferings, all the way up to national and international economic costs.

More recently in July 2022, the Institute of Government & Public Policy (IGPP), ran a dedicated mental health in construction event, which presented on topics such as: workplace culture and cultural change, understanding and reducing stigma around mental health, leadership approaches and corporate strategies to better support the mental wellbeing of construction workers (IGPP, 2022). Research and policy discussions along with more open dialogues into mental health in the construction sector is gaining momentum. However, the intricacies around mental health in the construction industry are complex and multi-faceted, which include various risk factors such as: strenuous and taxing working conditions, work-related stress, anxiety and depression, insecure self-employment contracts and varying levels of access to family and work support (Burki, 2018; Chan, Nwaogu & Naslund, 2020; Tijani, Jin & Osei-Kyei 2022). Furthermore, as explained by Chan, Nwaogu & Naslund (2020), employees often experience several risk factors simultaneously, thus further compounding the negative impact upon that employee’s mental health. Solutions are needed that target risk factors collectively rather than look to treat risk factors in isolation.

Given the complex interrelations between varied and compounding risk factors, coupled with research on mental health within the construction sector being very much in its infancy (Burki, 2018), this research aimed to gain further understandings in these areas. This project was interested to hear from the front-line construction workers themselves; those who are responsible for the manual aspects of construction work. Despite growing attention in this field, there remains limited understanding on how the risk factors listed above affect the mental health of construction workers in different job roles, contract types or profession status (Chan, Nwaogu & Naslund, 2020). Accordingly, this research project held the following three Research Objectives:

- To explore male front-line construction industry employees’ perceptions of what mental health means to them.

- To identify both positive and negative factors that contribute to experiences of mental health amongst the construction workers

- To gain insight into the interrelationships between the key factors identified

Research Methods

Given the focus upon exploring the perceptions and experiences of mental health in male construction workers, this research adopted a qualitative approach. Qualitative research creates insight into individual’s lived experiences, enabling exploration into behaviours, attitudes and beliefs (Gribich, 2013; Kalra et al., 2013). Interviews remains a popular and dominant technique within qualitative research (Opdenakker, 2006), and so for this research, semi-structured face-to-face interviews were conducted with front-line construction workers.

However, the topic of mental health can be highly stigmatised. This means that it may be difficult for

respondents to talk openly and honestly about the topic, which could jeopardise the research project. To address such an issue, Seidler et al., (2017) stresses that creating a safe and comfortable environment for men to discuss mental health is essential. Therefore, the main advantage of conducting interviews for this project, was to allow a private and safe space whereby the respondents can voice their perceptions in their own words and in a comfortable, one-to-one setting, to a researcher not affiliated to their company nor industry. Prior to the start of any data collection, the proposed research and methods were submitted to the university’s ethics committee and ethical approval granted.

Convenience sampling, also known as purposive sampling, was the method used for this

research. This is a popular method whereby respondents are selected based on convenience, as they are in the ‘right place at the right time’ (Acharya et al., 2013). Convenience sampling was employed, as on the day that research was collected, the site manager simply asked if any male employees wished to take part. Several male employees came forward and in total, six interviews were conducted with male workers in the following job roles: labourer, joiner, welder, machine operative and ground worker. Table 1 below provides an overview of the six male interviewees and their demographic information.

Table 1. Demographic Data of the Six Interview Respondents

| Respondent | Age | Role | Length of Time in Construction | Contract Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent A | 33 | Groundworker and Welder | 10 Years (Approx) | Self-Employed |

| Respondent B | 30 | Groundworker and Machine Operative | 6 Years | Self-Employed |

| Respondent C | 28 | Labourer | 5 Years (Approx) | Full-Time Contract |

| Respondent D | 23 | Labourer | 6-7 Years | Self-Employed |

| Respondent E | 61 | Labourer and Joiner | 44 Years | Self-Employed |

| Respondent F | 54 | Joiner | 30 Years (Approx) | Self-Employed |

The sample of six male construction workers were asked a series of questions during the face-to-face interviews. Table 2. below provides a summary of the sets of questions that were asked during these semi-structured interviews. However, as the interviews were only partly structured, this provided space for respondents to deviate from the line of questioning to bring in other relevant aspects to the discussions. This approach therefore provided a level of freedom for respondents to talk about what mattered most to them within the context of men’s mental health in the construction industry.

Table 2. Summary of the Interview Schedule

| Section A: about the participant | Section B: perceptions of mental health at work | Section C: perceptions of work policies and procedures |

|---|---|---|

| The interviews started with several ice-breaker questions about the participants job role, length of service and contract type. A brief discussion also took place about how the individuals’ career history and their experiences over their career in the construction industry | Respondents were then asked about their own personal understanding/definitions of ‘mental health’, how much of a priority mental wellbeing is to them and their overall views on discussing mental health with co-workers and managers. | The final set of questions focused on the support available from managers, HR and the construction company. The elicited discussions about awareness of policies and procedures supporting mental health at work and access to support. |

Once the interviews were completed, Braun & Clarke’s (2006) ‘six phases of thematic analysis’ were then used as a framework for analysing the interview data. This thematic analysis aided in identifying key themes from the 6 male respondents who all work in the construction industry based in the North-West of England.

Interview Findings

With regards to employees’ perceptions of what mental health means to them, the results show a surprisingly well-informed and positive outcome. Generally, the employees had a good idea of the definition of mental health, were able to explain what this means to them and the impacts it has on their day-to-day working lives. Awareness of mental health amongst the respondents was high and the respondents described their general perceptions of mental health in the following ways:

“Mental health to me is any frame of mind that you may be in that takes you away from your natural way of thinking or moving. So, for example, if you’ve got a fresh clear head you know, you tend to function more adequately than you would do if you were stressed or depressed or you have anxiety……..mental health, it’s quite a broad subject, isn’t it? There are loads of different ways that we can maintain it.â€� Respondent A

“I’d probably describe it a little bit similar to your physical health but whereas, you might have like a sore knee, you could describe a bit of a mental pain as worry and stress and things like that. I’d describe it as probably, like your state the mind how you feel at a given point, whether that be, I feel happy, I feel sad, I feel angry, it could be a range of things.â€� Respondent B

“Everyone suffers with mental health, every single person. Everyone’s got their own little things with mental health which will include how they feel and how they how they cope. If I’m not up to scratch or coping with my mental health, then it affects my day-to-day lifeâ€�. Respondent C

In summary, the construction workers had a good understanding of what mental health means. All respondents were able to clearly explain what mental health is, with clear acknowledgement of how mental health is just as important as physical health. Previous research had concluded that the topic of mental health is overlooked by males within in the industry, but this is not due to ignorance as respondents had well-informed answers and felt able to speak openly about the topic. This may mean the issues that the industry is experiencing in relation to high rates of mental illness may not be attributed to a lack of awareness of mental health. Whilst it’s hard to generalise from such a small sample, the trend supports that construction workers may not need policies to raise awareness of what mental health is, instead those resources could be redirected to where more support is needed.

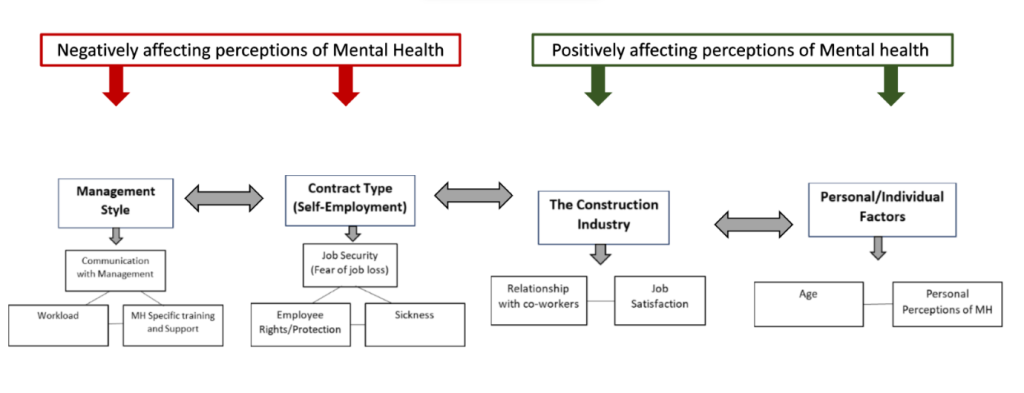

The next part of the interviews sought details on the positive and negative factors that contribute to experiences of mental health amongst the construction workers. Similar to the work of previous researchers in this field (Burki, 2018; Chan, Nwaogu & Naslund, 2020; Tijani, Jin & Osei-Kyei 2022), these findings also support a wide range of factors which are summarised in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. The positive and negative Factors identified to influencing mental health within the North-West Construction industry.

Figure 1 shows the common factors identified by the male workers as contributing to mental health within the construction industry. The factors have been categorised into clusters and whether these factors are affecting perceptions of mental health in a positive or negative way, which are discussed in further detail below.

- Positive Factors

There were some factors that appear to be contributing to positive perceptions of mental health, which had not been mentioned in previous research. These include the high levels of job satisfaction and strong, positive relationships with co-workers on site. Although levels of job stress were high, respondents expressed how much they thrive from the job satisfaction achieved by the project-by-project nature of working within the sector. The interview findings also suggest that workers value their relationships with one another and would feel a lot more open to discussing mental health issues with each other due to a higher level of shared understanding between colleagues:

“I’d feel more open to the idea of talking to them [co-workers]. They’re just like me, we get up, we’ve got bills to pay, we’ve got families and things like that and they’re probably going through a lot of the same things that I’m going through, so I’d feel more likely to open up to people like that.â€� Respondent B talking about co-worker relationships

“It’s the fact that I’ve created something, I get satisfaction out of it. I get the most enjoyment when the client is happy. If the client says I am absolutely made upâ€� Respondent F commenting on job satisfaction

- Negative Factors

There were however many negative factors identified by the construction workers, including the contract type of self-employment, lack of workers rights, high workloads, attitudes towards sickness and fears over job and pay security:

“They want the most out of you in an 8 hour or 10 hour window, like they’re paying you X amount per hour and they want so much work done on these jobs and sites. It’s like they will whip you until you’re just blood, sweat and tears.â€� Respondent A

“If you don’t work, you don’t get paid and that in itself creates more problems. If you’re feeling down for whatever reason, then next week I’m going to have even less money. It just creates more stress. I feel like if you did take a day off for your mental health a lot of people who feel like it would hinder their mental health more.â€� Respondent B

Another factor negatively influencing perceptions of mental health is management style, which includes general communications with management as well as overall feelings of support from line managers:

“I have took time off for my mental health in the past, they were awful about it. When I’ve gone back into work I wasn’t supported in any way. I heard the manager even laughed about it behind my back.â€� Respondent C

“I wouldn’t say too many people have been up to me in my working career asking if my mental health is alright. With regards to supervisors and managers coming round and daily or weekly asking if everyone’s mental health and well-being is OK, it’s not really heard about. I think management would be more concerned about a trip hazard than about how your mental health isâ€� Respondent A

It was stated by several respondents that more mental health specific training and regular site visits to check on the welfare of workers is needed as this could help improve the current crisis:

“You do see when on site, you will see posters and things like that, but very minimal. It’s all well and good putting a poster up, but there should be specific people visiting sites to make sure that they’re okay, even if it does mean dragging them in for a little 20-minute conversation to check in on them.â€� Respondent D

“More site visits are needed, definitely more site visits. You know, obviously arrange it with times and dates and everything. Obviously, it needs to all be addressed. The option and the opportunity should be there for the lads on site, where they can sit down and address these things� Respondent F

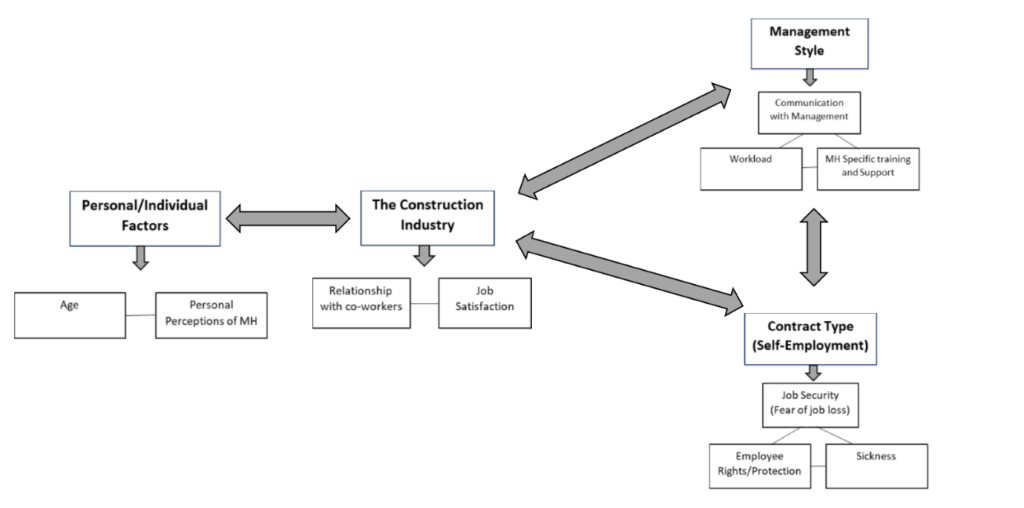

As previous researchers Chan, Nwaogu & Naslund (2020) had found, construction workers don’t experience negative factors in isolation. Instead, workers may be facing several risk factors simultaneously, which only intensifies the negative impact upon that employee’s mental health. The interview responses did support a relationship and hierarchy of risk factors, i.e. not all factors pose equal amounts of risk, some are more heavily weighted than others. The main connection was found to be between the Construction industry itself, self-employment contracts and overall management style and approachability. These three factors directly affect and impact one another. The contract type of self-employment is directly related to the construction industry, however the perceptions towards the factors that fall within self-employment (job security, attitudes towards sickness and employee rights and protection) depend highly on management style and vice versa, management styles and support can influence the construction workers perceptions of the workplace and impacts upon factors on their mental health. Figure 2 below shows these interrelationships.

Figure 2: The interrelationships between the identified mental health risk factors

As such, the findings support that if respondents have a good relationship with a supportive line manager, who can make the workers feel protected in their employment with a manageable workload, the other aspects of mental health can be more readily resolved.

Conclusion

This project was interested to hear from the front-line construction workers to gain a deeper understanding of the risk factors which affect the mental health of these workers based in the North-West of England.

The area of men’s mental health within the construction sector is a relatively new research topic, but there have been several insights that have emerged from this research. The first is that construction workers in the North-West have a good understanding of the importance of mental health and the awareness of what poor mental health can do. Secondly, the construction workers revealed some factors that positively affected perceptions of mental health, including high levels of job satisfaction and strong relationships with co-workers. However, there were more factors that appeared to have a negative influence on mental health: the contract type of self-employment and lack of employment rights that accompany this, along with poor management practices, which result in a lack of communication nor support to their workers. This concerning issue of poor relationships between management and their workers is an area that should be explored further, and this could be an overarching risk factor, which with more education, training and support for managers, could alleviate the poor mental health outcomes for front-line construction workers.

References

Acharya, A.S., Prakash, A., Saxena, P. and Nigam, A., 2013. Sampling: Why and how of it. Indian Journal of Medical Specialties, 4(2), pp.330-333

Braun, V. and Clarke, V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology, Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), pp. 77–101.

Burki, T., 2018. Mental health in the construction industry. The Lancet Psychiatry, 5(4), p.303

Campbell, M. A. & Gunning, J. G., 2020. Strategies to improve mental health and well-being within the UK construction industry. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers -Management, Procurement and Law. 173(2), pp.64-74

Chan, A., Nwaogu, J. and Naslund, J., 2020. Mental Ill-Health Risk Factors in the Construction Industry: Systematic Review. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 146(3)

Gribich, C. 2013. Qualitative Data Analysis: An introduction. 2nd ed. London, UK: Sage Publications.

IGPP (2022) Mental Health in Construction 2022. Online Event 14 July 2022. E-resource available from: Mental Health in Construction | 2022 Construction Series | IGPP

Kalra, S., Pathak, V. and Jena, B. (2013) Qualitative research. Perspectives in Clinical Research, 4(3), p. 192.

Kotera, Y., Green, P. and Sheffield, D., 2019. Work-life balance of UK construction workers: relationship with mental health. Construction Management and Economics, 38(3), pp.291-303

Opdenakker, R. 2006. Advantages and Disadvantages of Four Interview Techniques in Qualitative Research, Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 7(4).

Rees-Evans, D. 2020. Understanding Mental Health in the Built Environment. CIOB report 11th May 2020. E-resource available from: Understanding Mental Health in the Built Environment | CIOB

Seaton, C., Bottorff, J., Jones-Bricker, M., Oliffe, J., DeLeenheer, D. and Medhurst, K., 2017. Men’s Mental Health Promotion Interventions: A Scoping Review. American Journal of Men’s Health, 11(6), pp.1823-1837

Seidler, Z., Rice, S., River, J., Oliffe, J. and Dhillon, H., 2017. Men’s Mental Health Services: The Case for a Masculinities Model. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 26(1), pp.92-104

Sharac, J., Mccrone, P., Clement, S. and Thornicroft, G., 2010. The economic impact of mental health stigma and discrimination: A systematic review. Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale, 19(3), pp.223-232.

Tijani, B., Jin, X. and Osei-kyei, R., 2022. A systematic review of mental stressors in the construction industry. International Journal of Building Pathology and Adaptation, 29(2), pp.433-460.

Comments are closed